Garrett Bowman

My foot’s in the stirrup, my horses won’t stand.

G’bye ol’ partner, I’m leavin Cheyenne.

That’s an excerpt from an old cowboy song called I Ride an Old Paint. The song itself embodies the old west and the sense of restlessness that defined the American Cowboy. That same sense of restlessness had taken hold of hearts across the World and drove them onward in pursuit of Manifest Destiny, exploration, and settlement of the Americas.

Old Paint belongs mixed in with the stories of the American West. Stories of mountain men, wagon trains, dangerous adventure, and hopeful wanderings. It’s moving to think of the pure adventure, unimaginable risk, and the hardiness of the frontiersmen and settlers as they went out from their civilizations and into the wilderness.

As I look back on my own youthful adventures, I feel a stirring of emotion when I stumble across place names such as Bozeman, Nez Perce, Wallowa, Salt Lake, Laramie, Durango, Santa Fe… I feel an urge to once again seek out a stark, wide open view of the plain or desert, climb the spine back of a wind blasted mountain range, and rest in the dark black timber towering above a lonely valley with soft needles to lounge upon.

In 2019 it is reported that the US travel and tourism industry generated 1.9 trillion dollars in business. It would seem that I’m not the only one that has a tinge of wanderlust. But where does it come from? Is it something learned from years spent as a consumer in a market obsessed with glorifying travel? Do we have a need to see white beaches, ski in towering mountains, or tour the great cities of the world?

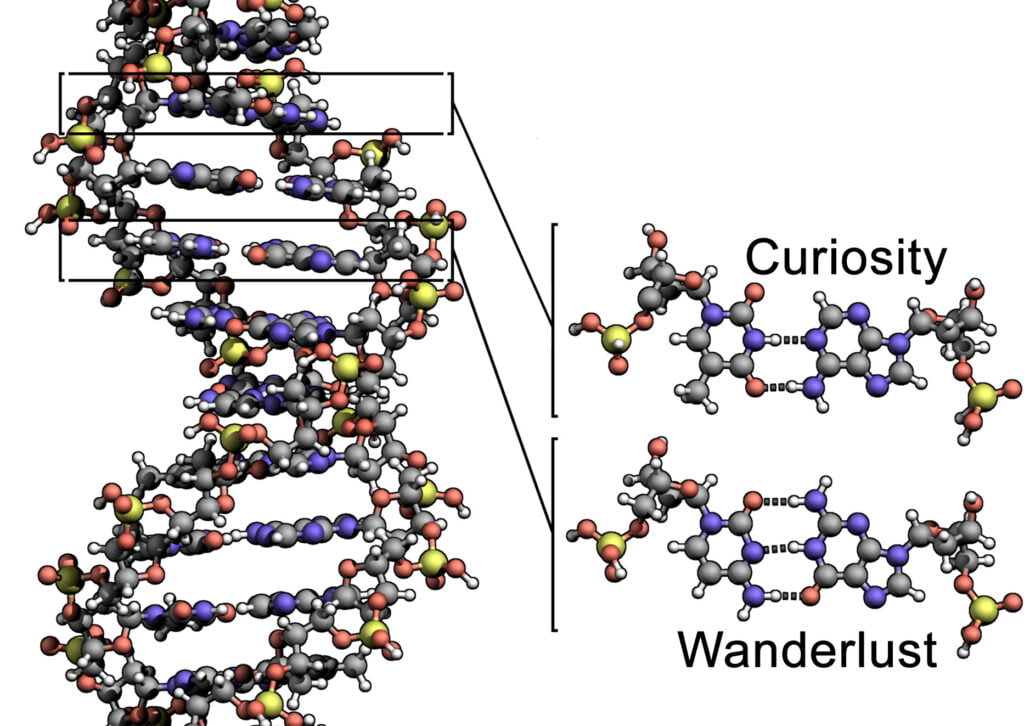

Maybe we don’t have a need per se, but perhaps the reason these things are so appealing to us is due to an internal hard-wiring that has been handed down generation to generation. Not just since the Age of discovery, but for thousands of years. As it turns out, humans have been on the move since the beginning. It may quite literally be in our DNA.

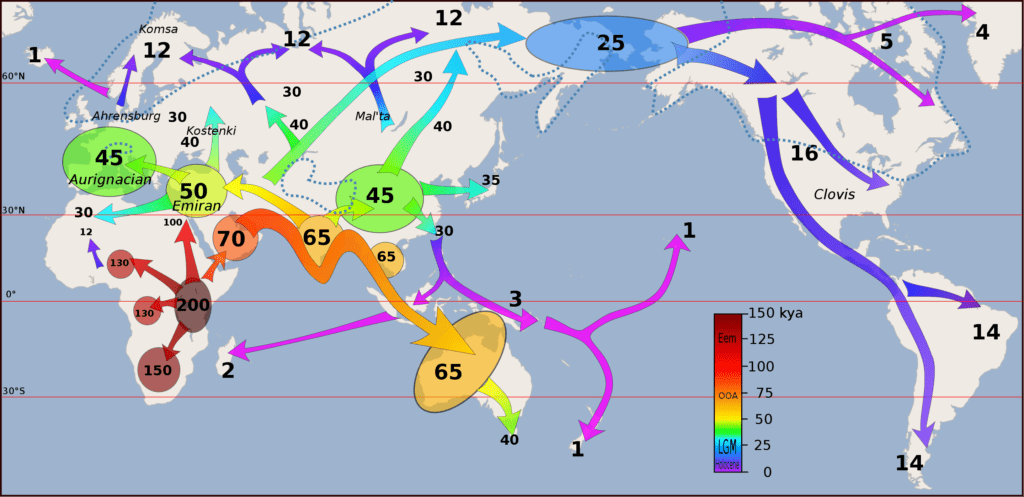

Where science meets anthropology and archaeology, we have come up with several intriguing tools to learn about our history. Archaeologists and scientists have been able to follow the movement of Homo sapiens as they exited the African continent 60,000 years ago. Breakthroughs in science have opened up new avenues to allow insights into our history. Radiocarbon dating, thermoluminescence dating, and dendrochronology techniques coupled with careful and accurate excavation offer reasonably accurate data to identify timelines. But, perhaps the biggest breakthroughs in evolutionary science have come from the study of mitochondrial DNA in the fields of human paleogenomics, evolutionary genomics and paleoanthropology. Human DNA has been collected from archaeological sites throughout the world along with the necessary matter to estimate accurate dates for the sites. Through careful mapping and study of the mitochondrial DNA from these finds, scientists have been able to piece together a reasonably accurate timeline of our quest to colonize the world.

Although we have a lot of work to do collecting and refining data, it seems modern humans left the African continent and moved into the Mid East and Asia 60,000 years ago. By 40,000 years ago humans had entered Europe, Indonesia, and Australia. 15,000 years ago they were able to pass from Asia to North America and then to South America. With more evidence, the timelines and specifics may change, but one thing is for certain; our ancestors were on the move. But why?

There are several reasons used to explain the migration of Homo sapiens, and our colonization of the world. It’s not likely that we can pin down such a complex subject with a simple explanation, but what all of the explanations have in common is pressure. Climate change, competition, conflict, even wanderlust. They all provide pressure that may have motivated humans to move in the search of comfort or survival.

Looking back at the first modern human societies, we largely see semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer type organizations somewhat similar to the first nations of the United States and Canada. Small groups of humans would migrate seasonally following game and forage, essentially following their sources of sustenance throughout the year. There’s no evidence of organized agriculture or the large settlements that stem from that movement. Those are both relatively late inventions on this time scale. It’s fairly easy to construct a scenario, then, where changes in climate, overpopulation, overuse, and conflict could cause people to move on to greener pastures. Much in the same way that today large populations still flee before invading armies and away from natural disasters. People relocate or engineer new ways to escape from rising waters and drought conditions. There’s no reason to suspect that our ancestors reacted any differently to their pressures, and the fact that they actively migrated throughout the world strongly supports the theory.

As technology progresses and the world becomes more peaceful, we don’t have the same pressures that an early hunter gatherer society would have. But after thousands of years, it looks like moving is a tough habit to break. We’re still drawn to new places, seemingly built to explore our surroundings.

Our eyes are now set on the stars. We’re turning our technology to the sky in search of the next adventure. Who knows where our wanderlust will take us. Almost certainly we won’t be confined to our own planet in the near future. Then it seems only a matter of time before we escape our solar system. It may seem like a stretch, but we’re adventurers with thousands of years experience. So next time you feel a thrill at the mention of a city, a longing for a mountain vista, or look out into the stars with wonder; know you aren’t alone. It seems we’ve always shared this trait with our ancestors right from the beginning.