There’s dangers in them there mountains. And the danger doesn’t just exist in the big mountain ranges, but in the small ones too. In this post, we will discuss how to navigate and read those snowscapes safely.

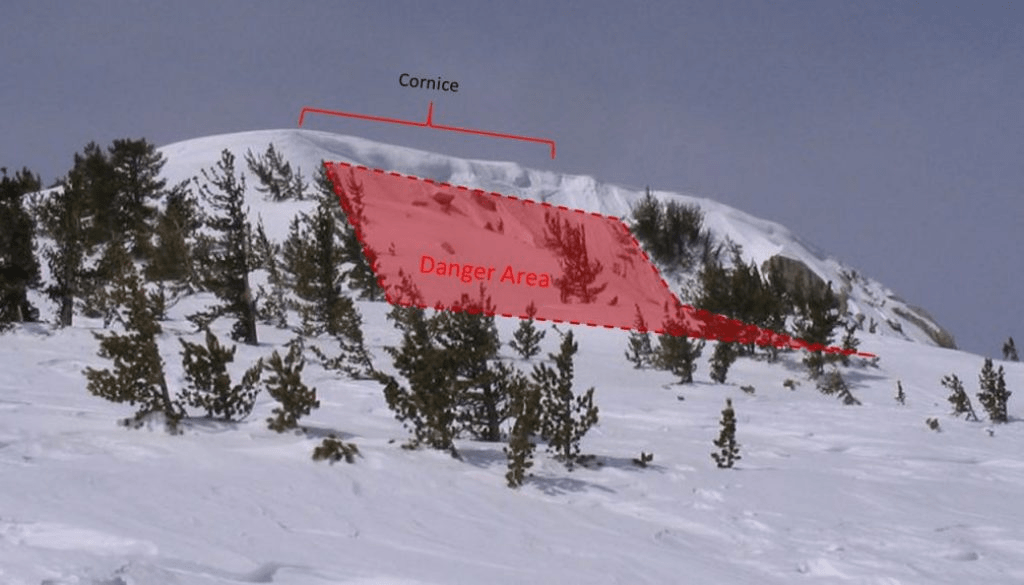

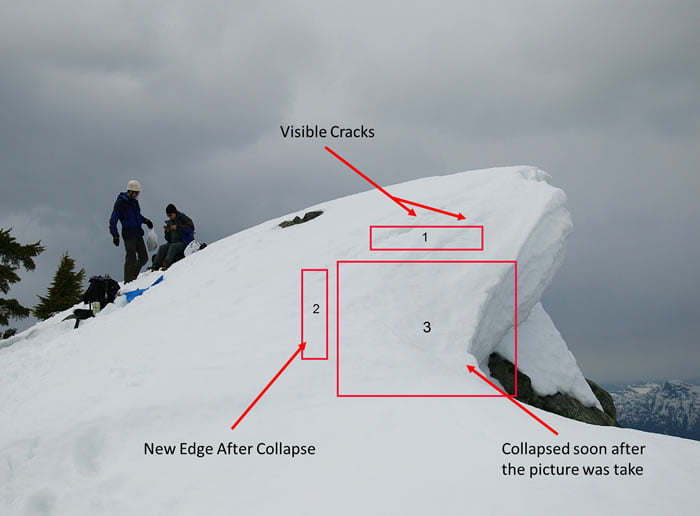

Cornices

The first formation we will talk about is cornices. Steer clear of these wave-shaped snow deposits often found hanging over a ridge’s leeward side (non-wind exposed side). Cornices can collapse under a persons weight, causing an avalanche. Travel as far away form the edge as the ridge allows. Also, avoid passing beneath them when you’re ascending a slope, making sure to stay out of the fan-shaped runout zone of a potential slide.

Safer Slopes

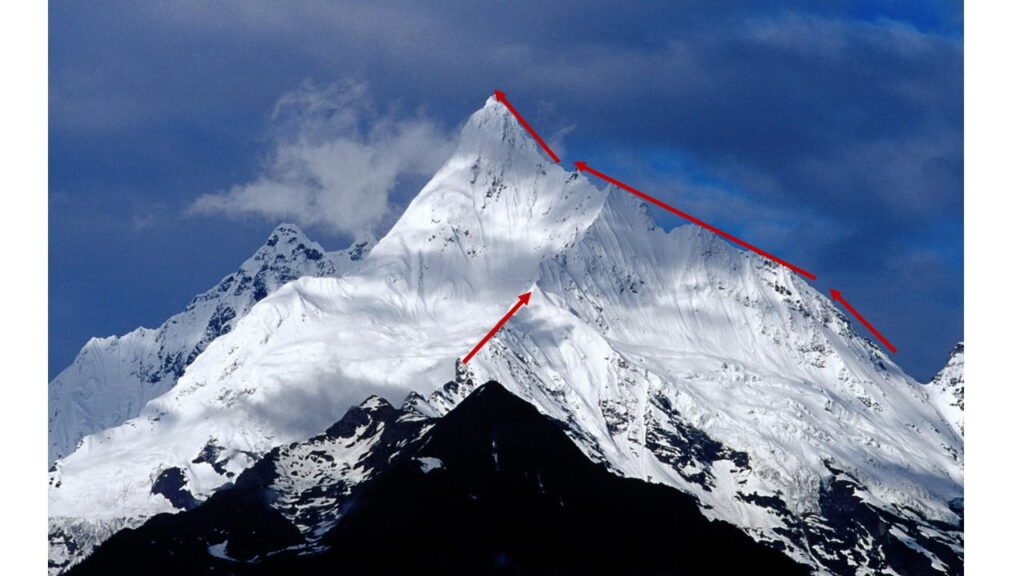

Look for windward faces (exposed to the winds) pitched 25 degrees or less. Sunny, south faces (#2) often stabilize sooner (this includes small less mountainous areas). To ascend, either beeline up (quick) or switchback (less effort). If breaking trail is too much of a chore then go straight up, with firm, easy to kick snow – zigzag. Steep faces (#1) may prove too difficult, find an alternative.

Ice

Before crossing a frozen river, carve out a chunk, or heave a big rock on it; the ice should be four-plus inches thick. As you walk, tap the ice with a pole; a hollow sound means thinness. Watch for standing water, slushy snow or dark patches (signs that a spring has weakened the ice). Avoid inlets, outlets, outer bends and rocks, which correlate to rotten ice.

Mountain Faces

Slides occur most often on slopes between 30 and 45 degrees, but can release on slopes as mild as 25 degrees, so pack an inclinometer and know how to use it. Leeward slides of ridges and the areas under cornices also get perilously wind-loaded, if you’re traveling in any country, there’s no substitute for using a beacon and getting professional training – find a course at avalanche.org.

Couloirs

These gullies can sometimes let you bypass steeper, more treacherous terrain. But they also can funnel rocks and snow right down on your head. Before heading into one, assess the slope angle – steeper than 30 degrees means risk. Stick to the sides, away from the major fall line through the center and always wear a helmet. Couloirs are safest in the morning, when snowpack is more consolidated; start early, carry an ice axe, and pack crampons in case of ice.

Ridgelines

The easiest route to a summit often lies along a ridge. Less snow accumulates there, which can make it safer than a bowl. Still, winds tend to whip ridges intensely, and cornices pose danger, too.

Forest

Dense trees can anchor snow, making slopes less avalanche-prone. But a big slide can easily topple trees below. Look for broken limbs on the uphill side of trunks – a sign that avalanches often barrel through. Also, watch for spruce traps (tree wells), hidden “caves” that form around trunks when the tree warms, melting the surrounding snow under the surface. Fall into one, and you can break a leg or get trapped.

Tree Wells (Spruce Traps)

A tree well is a void or area of loose snow around the trunk of a tree enveloped in deep snow. Also known as “spruce traps”, these voids present danger to hikers, snowshoers, skiers, and snowboarders who fall into them.

Increasing the likelihood of formation, coniferous tree branches shelter its trunk from snowfall, allowing a void or area of loose snow to form. Low-hanging branches as on small firs further contribute to forming a tree well, as they efficiently shelter the area surrounding the trunk. Such wells have been observed as deep as 20 feet. They can also occur near rocks and along streams.

Tree wells may be encountered in backcountry, on ungroomed trails, off-piste, and on ungroomed/piste boundaries. The risk of encountering one is greatest during and immediately following a heavy snowstorm.

Victims can get trapped in tree wells and become unable to free themselves. In two experiments conducted in North America (by the NW Avalanche Institute) 90% of volunteers temporarily placed in tree wells were unable to rescue themselves.

Frequently victims end up in wells head first, complicating recovery efforts. Often they are injured in the process, suffering joint dislocation or concussion.

See also: Skis or Snowshoes? Consider Skishoes, Rigging a Pulk the Right Way