I heard of the long winds that build in the Rockies, racing down and spending their force on the Great Plains. Winds that move stone, leave only the strongest, twisted and gnarled trees on the mountainsides. Finally to subside then gently buffeting the hay fields and crops of the foothills and flatlands. Growing up on the shores of Lake Michigan, I know there is another brand of long wind that belongs solely to the Great Lakes. It comes with low grey skies. Wind that blows hard and continues to blow unchecked until it reaches the sandy bluffs. Firm wind that’s steady and never less, a constant pressure, gusting at times, but never for an instant calming. An invisible wall that sets everything to movement. An unending wind that changes water, coaxing it into a remorseless blind rage, eager to destroy anything that will not yield. Chased from the depths; cold, dark, green water racing to outpace the boiling grey clouds. Growing and stacking itself in rows upon rows of fast, white topped waves desperately trying to climb the backs of each other. Leaning to the strong steady wind, it slaps and cracks at the ears and tears at clothing. Eyes squinted to the blowing sand, the surf beckons, and an irresistible primal fear keeps you away. Waves build to incredible heights, stacking up, and tearing themselves apart on the beach just in front of you. Filled with an awe, admiration, a subtle abhorrence, an instinctual sense of dread. Beauty, power, and destruction unfolding before your very eyes. You know that it is unfair and unrelenting. It does not favor you, any man, or any thing; and will not hesitate to destroy the unwary like it has so often in the past. We shrink from the indiscriminate fury of the long winds that belong to the Great Lakes. A force humbling to behold, and best beheld from a distance.

Stepping out of the truck in the parking lot at the Inland Seas Education Association building, I looked around for the familiar faces I was expecting. The beginning of a Fortune Bay adventure is always a good time. No matter who shows up, you’re bound to be surrounded by type A people, all excited and ready to take a normal trip a bit too far. Sharp, intelligent, capable people, good folks all around, and the ones you want to ride the river with.

After a few greetings, gear begins to pile up on the pavement. A jolly roger flag is produced and planted atop a mountain of bags and gear. Eye patches and kerchiefs are handed out. Spirits are high as we all talk about what is expected to be a unique trip. No doubt we made a cutting figure as the crew of the Inland Seas Schooner rolled in. Not much past daylight, we milled around in outfits of all sorts from beach bums in swim trunks and flip flops, to cheap Halloween pirates complete with plastic eye patches and swords.

We piled into the company vehicles with our gear and headed for Northport. Most of the morning was spent enduring the bane of all forward progress; safety briefings. Turns out, these safety briefings are pretty important with all of the moving equipment aboard a 60’ double masted schooner outfitted like the Inland Seas. We set sail mid-morning from Northport heading toward South Fox Island. The water calm and breeze fair, we had a chance to learn about the operations of the ship and the different roles it served as a research and education vessel.

Built in 1993 the Inland Seas is outwardly modeled after the schooners that plied the Great Lakes in the 1800s. Steel hulled and quite luxurious, she’s a far cry from an old wooden sailing ship, but the satisfaction of replicating history remains. The 5 person crew was used to sailing with groups of children, teaching them about sailing and the Great Lakes ecosystem. At first, they had a hard time coping with the rowdy bunch of high energy adults, but they warmed up quickly as they realized we were very very low maintenance.

As we got used to each other, stories and plans began to flow. Our little expedition began to take shape. We would begin by a tour of the South Fox Light and grounds then attempt to reach a safe anchorage in the lee of Beaver Island before the weather began to turn.

South Fox Island rose from the horizon with the strange skeletal lighthouse tower floating above the tree line. High water had eroded the beach and begun to carry away the dune. Left behind is a four-foot-tall embankment right at the water’s edge that is studded with the roots of dune grass and the occasional bush or tree. Beyond the lighthouse grounds stands the prominent feature of the island; a high bluff, heavily timbered and looming far above the lighthouse towers. We anchored west of the light and the boat was lowered.

The zodiac could carry 6 people with their gear and the pilot, so it was necessary to make a couple trips to ferry everyone ashore. Before the first boat landed, a man was spotted walking barefoot down the dune toward the beach. There’s only one habitation on the island, which is rarely occupied, so the stranger’s presence was rather odd. On this remote island in the middle of Lake Michigan, it could only be Vlad. Vlad is one of the most interesting people you can meet, and he always turns up in the least expected places. He’s a Science teacher at a public school, but you’d never expect that by looking at him. At a middle height with shoulder length dark hair and a constant smile, he exudes positivity at all times. An easy Eastern European accent rounds off his magnetic personality. At once you spot a man that is both in touch with the world around him and enjoying every second of it.

Vlad accompanied us on the tour of the lighthouse grounds. Most everything on the grounds was in a fair way of disrepair. Heavily weathered remains of the lighthouse towers and their buildings seemed drab and dull as light rain started to fall. The Fox Island Lighthouse Association began caring for the property in 2006, and had made slow, but steady progress trying to restore the buildings while keeping things historically accurate. Built in 1867 as an aid to navigating between the beaver archipelago and the manitou passage. A traveler would have seen the brick building and tower at the southern end of the island. Standing out from the low sandy dunes that surrounded it the round tower, a beautifully crafted Fresnel lens would have flashed a slow red beacon.

What we saw now was low brush and oak trees that obscured the tower and most of the buildings. Only the skeletal tower brought from Georgia in 1934 could be seen from the water. The brick used in the 1867 construction of the light tower and keeper’s quarters couldn’t hold up to the long winds, blowing sand, and the freezing winters. It began to erode at an alarming rate, so another brick building was built around the original as a shell. Only instead of matching the masterful tapered cylinder of the original tower, a square tower was erected around the original. Stepping through the front door of the square light tower, you enter the interior of any classic Great Lakes lighthouse. Brick walls mortared over into a rough texture and heavily whitewashed. A beautiful cast iron spiral staircase with landings every 10 feet, once painted, but now rusty. An iron handrail, anchored solidly into the wall, that follows the curve of the wall and the contour of the steps. The cylindrical tower had portholes at each landing. They still exist, but instead of opening up to a view of lake Michigan, they only offer the solid brick wall of the exterior tower. Ascending to the lantern room and out onto the gallery you can see just how overgrown the area has become. Only a small vista of water to the south can be seen through patches of dense oak tops. The keeper’s quarters are arranged in Victorian style, with beautifully crafted crown molding, solid doors, hardwood flooring, and fine woodwork throughout. No doubt a beautiful building in its time. Now, the experience was eerie. Dark inside, with several windows boarded over, and 60 years of grime and decay upon the walls and floors. Paint peeling from the walls and devoid of furniture. We walked the halls and rooms shining lights around, held captive by curiosity, eager to view history, and half expecting to see something that should not be seen. Our tour ended with the old boat house and concrete pier that had been smashed by ice flowing through the straits. We made our way back to the beach where the boat was waiting to bring us back to the Inland Seas.

While we were on South Fox, the weather had begun to deteriorate. Anchored in the lee of the island, the ship was in calm waters, but it was apparent that the wind had begun to whip up the waves out on the open water. Large waves danced like mirage on the horizon all around us, but we remained optimistic; confident in our ship, crew, and captain.

At middle age, with curly hair, and stubble on his chin beginning to show grey; Captain Ben is a man of average height and well proportioned. His appearance serious, but positive, he takes after those who belong to a class of working men that pour their entire selves into their seasonal work. By the end of their hard season, they begin to fray a little at the edges, eager for the rest that they know is soon to come. Quick, decisive, and intelligent Captain Ben is stoic in his responsibilities, and clearly passionate for what he does. Standing at the helm, in a dark foul weather suit with a matching sou’wester pulled low over his brow, yarning with the first mate of sailing through poor weather around the world. He looked the modern counterpart of the very men that sailed the Great Lakes when they were the highways of the frontier.

Captain Ben gathered everyone at the back of the ship after dinner and explained the situation.

“We have 2 maybe 3 hours of open water and bad weather before we reach the calm water behind Beaver Island. That will put us in a good position to reach High Island in the morning. If you were our normal customers, we wouldn’t leave the shelter of South Fox, but you seem like you can handle yourselves.”

Set to work, we labored in teams hoisting the anchor using a manual winch to draw the chains back onboard. Attempting to make a fluid motion, one person would place a four foot long wooden bat into a slot on top of the winch while the other person having completed this step an instant before, heaved their lever towards the deck, rotating the winch a few degrees and taking up a couple links of chain. The whole process takes quite a few minutes.

Once the anchor was secure, we steamed for the lee of Beaver island, the ship’s diesel engine thrumming smoothly below deck. Leaving the shelter of South Fox, Southeast winds of 25 knots with gusts of 35 knots raced through the strait driving waves reaching 6ft.The Inland Seas labored along slowly under power, pitching and rolling sharply in the surf.

As the grey sky grew dark, the wind picked up. Instruments to measure the wind direction and force began registering gusts near 40 knots. What a force to behold first hand when the long winds descend upon the Lake. I stepped to the railing, no longer able to keep myself upright with my own balance. Darkening skies and screaming winds surrounded us in that open water. With fits of slashing rain and low turbulent skies, darkness began to fall early. Conversation could not be kept up on deck in the slapping wind. Captain Ben ordered the crew to attach lifelines running the length of the ship in case of emergency. Waves began to break and wash over the deck, sending torrents of water over our feet. Captain Ben ordered no one to go forward of the pilot house for fear of having someone washed over.

Knowing the battle with my equilibrium might be a losing fight, and certain to lose if I should find myself below decks during such conditions, I stood fast to the railing letting the wind, rain, and spray cool my face. Eyes fixed on the dim horizon, mesmerized by the reaching and clawing of breaking waves in open water. I had until this moment only seen these conditions from shore. I was taken back to my childhood when my father and I would fish these same waters. Our boat would have never survived.

Captain ben bellowed over the wind;

“If you feel like you are getting sick, make your way to the port side and heave with the wind, not against it. We’ve had that happen too many times.”

Light faded from the sky and the dim horizon disappeared. So did my senses. Fighting back the repulsive feeling, it finally overtook me. I braced myself low, and vomited over the railing. There is a momentary relief that comes to the seasick person just after they give in to the feeling. For a moment, they are OK, if their conditions change for the better, they can recover. Our situation would not change, not for two maybe three hours. I embraced the momentary relief, knowing that it was only the beginning of a very long night for me.

The ship rolled hard. The side would dip and a wave would wash the deck with ankle deep water, a few short seconds later I would be ten feet or more above the waves and descending rapidly. The second round of vomiting came on. This time I knew that I had expelled everything in my stomach, and tried to force water down in the moment of relief. The rain picked up. Cold and driven by the wind it began to cut and soak into anything that was dry.

“There are three types of fun.” Said Captain Ben “We had a group of boy scouts once and their motto was; there are three types of fun; 1: Fun right now, and also fun to look back on, 2: not fun now, but fun to recall at a distance, and 3: no fun now, and no fun later. We will see what kind of fun this shapes up to be.”

Most everyone was in high spirits, reassured by the words of the Captain. We tried to laugh and speculate on what type of fun we were having.

The third wave of nausea hit. I lost all of the water I had tried to keep, and the bile from the dregs of my stomach. I knew now there would be no period of relief. I tried hard to drink water, knowing that it was only going to be worse when I couldn’t.

It was now when I began to recede inside myself, no longer aware of the shouted conversations near the pilot house, barely alert to the helping hands that passed my water bottle back. Now only a part of the heave and roll. Knuckles white, gripping hard on the wire railing trying to remain steady.

I started to dry heave. A tightening of the stomach, cramping, tight enough to crush a stone. Over and over, painful contractions, mindless gagging and coughing. My internal organs compressed to a singularity and not a drop to squeeze out, and no relief. Completely taken over by base animal instinct. Hold on, heave, cough, try water.

I was barely aware enough to notice Doc Piton had joined me at the railing. He must have noticed that I had nothing left to give, because he willfully gave his portion and more. Then there were others, maybe two or more, standing or sitting near the railing in the darkness. I continued to heave pointlessly, becoming exhausted. Cold with rain and wind, empty. Empty inside and in mind. Cold, wet, sick, cramped, holding on, drink water.

At some point our condition improved, I was aware of the crew moving around on deck. Aware that it was possible to move around on deck. We had reached the lee of Beaver Island. My sickness gradually faded to cold and exhaustion. I went below, found my bunk, and without even bothering to unlace my boots, lay down to sleep.

I woke shortly after dawn the next morning feeling pretty good considering the circumstances. Everyone’s gear had been tossed around the cabin in the storm the night before. Everything was hastily stowed in the dark. Instead of sharing a bunk with my bags I found myself with Doc Piton’s drone, someone else’s pack, and a box full of writing materials and science equipment. I looked up some dry socks and went topside.

We were met with a beautiful morning. Restitution for the evening before. Winds were still high, but beginning to change direction. High cumulus clouds raced by in packs reaching to the horizon in every direction, moving faster than the already fast wind. Casualties from the tossing of the night before rehydrated while we made a plan for the day.

It was decided that High Island was our best target for the day. An easy sail from where we were anchored, it offered safe anchorage for another set of storms that were supposed to reach us in the afternoon. High island was host to a number of people in recent history. Occupied by native American fishermen, a religious cult called the House of David, logging crews, and allegedly holding the treasure of King Strang. We were more than happy to make this stop on our tour.

Winds began to change direction, and we found an ideal anchorage in High Island Bay on the North East end. Unloading into the boat and arriving on shore, we found the main crop of all Great Lakes islands; poison ivy. Heading inland, we stumbled upon the old DNR research cabins that held state workers while operating on the island. They were quite derelict at this point having not been used since 2008. The roofs had begun to collapse, windows and doors broken. Although in poor condition, the interiors appeared to have been left quite intact. Old propane refrigerators, propane lights, canned food, and bedding were still left right where they were 11 years earlier.

Following old overgrown trails behind the cabins we began to make interesting finds. Coming first upon an old foundation near the top of a hill. It looked to be positioned at an old crossroad. Just two high areas that came together, but shaped by more than mere coincidence. It must have been a large structure, seemingly open on one end, perhaps a barn. All overgrown and decayed now, covered in years’ worth of leaves and nature’s refuse. Towering oaks and beech all around, a mature forest with thin underbrush choked by the shade. An island that would have been absolutely clear cut in the 1800’s style of logging, now stood tall and proud. The wilds had retaken what they lost to man, covered his roads and knocked down his buildings. Following what we thought was an old roadway, we came across the remains of an old car. Now just a frame and rotten tires, we wondered what the story was. Was it part of one of the short lived civilizations that inhabited the island? Or was it some wreckage from the logging industry? With strange and brief modern history, and only the decayed trappings that remain, one can only guess what truth lies in the stories. We attempted to follow the roadway, but without a trail and a storm quickly approaching, bushwhacking became too time consuming. With no clear goals in sight, we decided to return to the ship.

Back aboard, a stern warning came across in the marine radio in a monotone robotic voice; “SPECIAL MARINE WARNING for Beaver Island and surrounding areas, NW winds 25 knots, gusting to 35 knots, heavy rain and high winds expected.”

A large storm front had formed in the NW over Canada and had been moving toward us for a few hours, wreaking havoc in the Upper Peninsula and building strength over northern Lake Michigan.

Winds began to pick up. Captain Ben assured us that we were in the ideal place to weather the storm, so we stayed put. As the ship swung wide on its anchor chain with the changing winds, a giant shelf cloud loomed over High Island, and raced to overtake us. The crew donned their foul weather gear and the lifelines were deployed. Although in an ideal anchorage, no chances can be taken against an unpredictable and merciless adversary.

The shelf cloud came pouring across the sky in a wide arc from both edges of our horizon. Boiling and rolling over itself, like a single breaking wave, it forced the blue sky back. It passed low, quickly over the island, covering the land and water in dark shadow. Ominous and black, a definite demarcation of where fair skies ended and danger began. The wind began to pick up, not fleeing from the storm, but instead rushing toward it as if the storm would pull in and consume the surface of the water and everything on it. The ship swung on its anchor chain. Now stern to, the storm broke upon us. All at once the sweeping wall of the storm cloud was above us and the wind switched direction. From a roar the wind began to shriek through the tight lines of the rigging and drive down sheets of rain. Out across the harbor, the rain battered in rhythmic patterns upon the whitecaps. Under bare poles the ship tugged at its anchor chain and the anemometer registered a gust at 38 knots. In a matter of a few minutes the worst of the storm had come and gone. A light rain played out over the calming waves. The wind died down to almost nothing. A moment later the sun came back out, and blue skies followed right behind what was left of the storm.

A call went up “Look at that!”

Head turning back toward the wake of the storm, the most vivid and complete double rainbow I have ever seen, spanned miles across the sky. Colors brighter than real life, visible from end to end, another incredible spectacle. After witnessing the focused fury of the shelf storm, added with the humbling experiences of the night before, glad to have been sheltered in this harbor, and in utter amazement at the phenomena before me; it is a moment in time that I will not soon forget. We stood in awe, not wanting to blink, not wanting to miss an instant of the gift we were receiving. Giddy with the joy of being. The whole ship was engrossed in the splendor of the moment.

As evening set in and the sun began

to fall closer to the horizon, we brought our instruments up on deck. With an

assortment of guitars, ukuleles, an electric bass, a jaw harp, and Captain Ben

to lead on his violin, we endeavored to extend the contentment and joy of the

day.

There is something about being able to create music as a group that makes such a positive bonding and lasting impact. I have rarely felt better than when playing with a passionate group of folks. Whether the music be good or bad, everyone shares such a positive moment, sucked into and engrossed in the task at hand. As we played now and shared great comradery, someone asked about the two younger crew members, Marcel and Jillian. They had seemed a rather quite professional pair, with no ties outside of their work with inland seas. After some prodding and prying, it came out that they were actually married, and this exact day was their anniversary.

Someone queued up “Can’t Help Falling in Love” by Elvis, and at the very firm request of the rest of the company, the couple was forced to share a dance. Showing their discomfort, aided by our collective dissonance, they wobbled stiffly about the deck for a few moments while the tender hearts aboard got their Awwwwws. The comedy of the whole situation lifted the group to elation and we settled in for a final song from Captain Ben, the sun set behind High Island. Darkness falling over the ship, Captain Ben began to belt out his famous rendition of Don Gato. The whole group joined in, and we wrapped up an extraordinary day on a high note, and in the highest spirits.

Once below, it was back to business. Gear was being stowed, people were turning in, and Captain Ben was looking for volunteers to stand anchor watch. I volunteered and stepped up to the wheelhouse to receive a briefing.

“Keep an eye on the depth and compass bearing. This graph will sound an alarm if we go in too shallow, or start to drag the anchor. Watch for other vessels coming in close. At the beginning of your shift, take note of the depth, compass bearing, wind speed and direction, and note any changes as your shift goes on. Wake me if anything gets weird. Other than that, enjoy the quiet time and the stars.”

I took a shift from 11 to midnight, so I turned in for an hour or so of sleep.

Below decks the accommodations were quite luxurious compared to most FBET trips. A galley with an ice chest, range, and good clean water. A countertop surface set up with scientific equipment for making observations and taking data from the lakes. A fairly spacious head. A common room with a table and ladder topside. Ten or twelve bunks line the walls, not much more than a place for your body, it was shared with your gear and any sand that you picked up during your travels. Plenty comfortable, and easy to use after a long day of fresh air and excitement. Shortly after dropping my head on my pack, which doubled as a firm pillow, I awoke to a whisper.

“You’re up for watch” and a faceless person stumbled through the dark cabin toward their bunk.

I rolled out and into my shoes and headed for the wheelhouse again. I wrote my measurements down and flipped through some of the old log books sitting on the desk. Stories from high school kids who took a trip with Inland Seas and stood an anchor watch just like I was doing. Simple stories of islands, activities, sailing, science; the stories of adventure that mark the relationship ISEA has with their customers.

Stepping outside I gazed up at the stars. Bright and clear with only a few small clouds. The moon having set hours before, not to appear again until early morning, constellations unknown to me played out across the sky.

I don’t think anyone is really alone on a clear night, at least anyone that can be with the stars. There’s the big dipper, the opening facing Polaris. These are always present here. Not always obvious, but never not there. I wish I had seen the Southern cross that time in Mexico, but there were many storms, and I may not have been quite far enough south. Someday though.

It’s not very often that I need to use stars in the summer. I don’t spend time with them until the fall. In September and later we rise early with Orion and he guides us on our way out to the hunting grounds. Always South of East when you go out into the darkness and cool of the early fall mornings. As the season gets late, he lies to the South and to South of West when it gets dark again and he guides you as you trail your target. It’s easy to get turned around when you’re following spore, late night and tired. Focused on the harvest, searching for every sign, keyed in on everything except direction. The hunter’s belt is always South of west in the late hours to guide you on your way.

No, we’re never really alone on a clear night. Staring upward at these stars though, I do not know them. They will always be here for me. Perhaps I should get to know them, but that can come later. I head back down into the dark cabin and roust the next person to stand watch.

Next morning after chuck, we sat down to make a plan. Captain Ben filled us in on the weather report for the upcoming days. He didn’t really see a definite break in the bad weather. Generally wet, very windy, similar conditions to our first night out. We had a choice: continue on our island hopping adventure, or stick close to the south end of beaver island and wait for a clearing to make for Northport. All of the same mind, we decided to sail for Garden Island citing a few contingency plans. Perhaps the weather would break tomorrow, perhaps in the worst-case scenario, anyone that needed to leave could take the ferry out of St. James.

The wind was strong from the north in the narrow strait between the islands. Cool, cloudy and spitting rain, it was fine weather to sail. We tied a furl in the mainsail and foresail in the bay at High Island and lined up to run the anchor winch. Once the anchor was stowed, we turned to hoisting the sails. In a line at the rigging for each mast, we waited for orders.

“Haul away peak! Haul away throat!”

Each team hauled hand over hand on the ropes that raise the sails. As the sails rose, they filled with air, the ship began to lean.

“Avast peak! Avast throat! Drop behind!”

All but the first in line dropped the rope. Standing up front you hold tension as a crewmember puts a turn of rope around a post for friction.

“Heave!”

Leaning all your body weight into

the rope, the crewmember pulls up the slack and secures it.

With the sails fully set, Captain Ben instructs the crew to position them to provide maximum efficiency. The ship leans further, the sails fill to a tremendous tension, and we make steerage. Soon we are breaking through waves, canvas slapping, rigging ringing on metal masts. Starboard deck only inches from the surface of the water and the port several feet above. She pushed through the surf, sailing well, rolling slightly on the confused waters, sometimes slamming hard into an oncoming wave. Wind whipped around us and stiffened the sails with a tremendous force that moved the ship smoothly forward.

We were coming even with the North end of Beaver Island when the crew got into position to change tack. Wind buffeting at the ears made any other sounds indistinct and conversation impossible. As we turned toward the wind, Captain Ben bellowed over the wind

“Ready to tack?!”

From their positions forward the crew could be heard faintly;

“Ready!”

Captain Ben listened and observed the crew at their stations. Then sharply, clear over the wind and waves;

“Helms Alee!”

He threw the ship into the wind with a quick turn of the wheel. As the bow edged closer to the wind the sails began to slacken and the ship began to lose momentum. The sails began to luff. Gently at first, slowly relieving the massive tension, then violently whipping back and forth like giant flags before our very faces. The booms being some 8 inches wide and perhaps fifteen feet long, began to bounce wildly and uncontrollably, attached to the loose and flapping sail, a certain death sentence for anyone in their way. Amid the noise of the slapping sails, the banging of the booms on their sockets, and the ringing of the rigging on metal, the waves began to crash and spray over the bow as we lost the power and momentum to cut through them. At the height of the violence, just as it seemed we would come to a stop, dead in the water and shaken to pieces by the wind and waves, the bow crossed over the wind. The sails filled again, snapping tight, straining the rigging that held them in check. The same tremendous force that seemed as if it would tear the ship apart worked on the sails, pitching the ship over to port and sending us on our way. The same maneuver had to be repeated two more times before we came up with Northcut Bay on Garden Island. We anchored in calm waters, humbled and awed again by the impressive forces at play on the Great Lakes.

We loaded into the zodiac and headed for shore. At the beach we decided to head for the old DNR cabins via the post office trail. We started along the brush choked trail and soon came up with the foundations of the post office that served Success Michigan, the short lived settlement on Garden Island. Standing in the ruins of the old post office you can’t help but wonder what the island looked like back then. People? Natives returning from the lake? Folks going about their business? Men of the logging camps? We drifted down to the DNR cabins, poked around at the beehives for a bit, then made the call to hike up and visit the Native American cemetery.

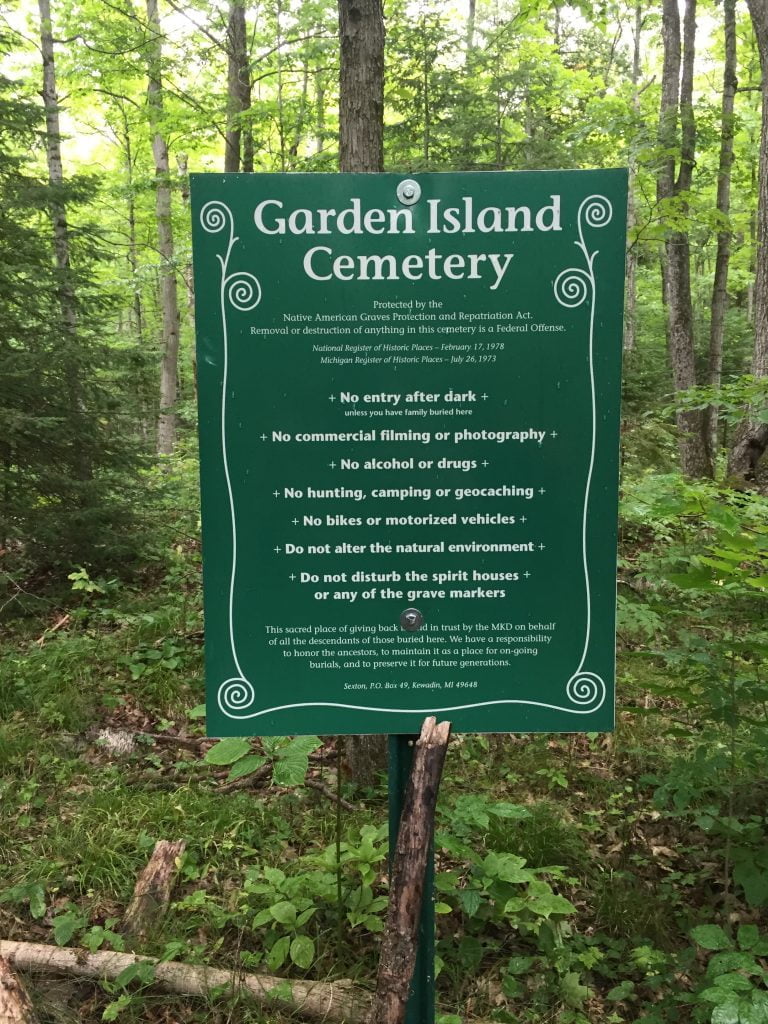

Hiking along, skirting the flooded trails and wading through the poison ivy that seems to infest all Lake Michigan Islands, we came up to a sign that marked the entrance of the cemetery. Lighting a cedar smudge in offering to the dead, we passed the boundary sign in reverent silence. Said to be the site of some 3500 burials, and one of the largest native American cemeteries in the United States. The area somehow seems in its natural state, very much like the rest of the island. None of the oppressive feeling of a modern graveyard with rows upon rows of monuments marking the passing of man and time. Quite overgrown; tall oaks, maples, and beech trees stand vigil over the randomly placed stone markers and dilapidated spirit houses. Wandering the area, you’ll find a cluster of old stone headstones dating from the late 1800’s. Just what you would imagine; small, round at the top, white, weathered, and with the names and dates barely legible. Here and there strange little structures jut from the ground in odd heaps. These are the spirit houses that serve as shrines for the departed. They blend into the landscape. Some mere piles of rotting wood, others with some integrity, but none without severe weathering. Walking on, markers become less frequent. Small depressions in the earth force the thought; am I standing on a grave, or the void left from the root ball of an overturned tree? A wild and natural place, remote and solitary with a great spiritual weight, but unkempt, unsheltered, and bare. Leaving the cemetery grounds, we made our way cross country back to the ship.

Back aboard and after supper, we deliberated on our situation. Nothing is guaranteed on an expedition with FBET, schedules and the weather are no exception. The storms and wind that had battered us the first night and kept us running from shelter to shelter were not scheduled to break. Captain Ben thought it not a very good idea to make the run back to Northport in the face of the current conditions, and had been working on contingencies for the last day or so. The Inland Seas was slated to be back at port the next day, some of the FBET crew had other obligations and needed to be punctual. Captain Ben suggested that if we couldn’t get a break in the weather and safely depart for Northport by tomorrow afternoon, those who needed to leave ought to take the ferry out of St. James. The ferry service runs pretty much regardless of the weather and would most likely ship out at the regular time.

Knowing that the forecast was dismal, and we’d probably be splitting up tomorrow, we all packed into the cabin to make the most of our last evening. Confident in the safety of our anchorage, we stowed our constantly wet gear and huddled up in the common area. Sitting awkwardly, laying on top bunks, standing in corners, sitting on the ladder, we were sharing chord sheets and playing all sorts of instruments. Ukes, guitars, Marcell with a jaw harp, first mate Bob with an electric bass, amp in one corner him in another, and Captain Ben’s famous violin. We played for a short few hours while it rained and blew outside. Captain Ben put on a fine show with his rendition of Long Hot Summer Days. We finally finished by belting Don Gato until the little cabin overflowed with joy and out into the stormy night. An anchor watch was organized and folks turned in for the night.

Next day we made a short run around the north side of Beaver Island into St. James harbor. Beaver Island and its settlement, St. James, have been the center of a unique American comedy or tragedy depending on how it’s viewed. A group of Mormons split from the church and settled there at St. James with their leader James Strang. Strang reigned as king of his tiny empire for six years; raiding and trading with the communities along the shoreline. Engaging in all types of criminal and unethical behavior towards the gentiles of the area, King Strang became rather out of control. Pillaging of coastal towns when the fishermen were away, murder, and forced conversion were all part of King Strang’s tactics. Details of what came next have never been fully confirmed, but we do know that Jesse Strang was shot and the two perpetrators fled to a US Navy ship anchored off Beaver Island. Strang died a few days later, and the two men stood trial in Mackinaw. They were both acquitted and a posse thought to originate from the fishing village on St. Helena Island in the straits of Mackinac ran the Mormons off of Beaver Island. This marked the end of the kingdom James Strang built on Beaver Island. No one knows if the assassins were hired by the U.S. government, or acted on their own, but popular support in their cause got them off scot-free.

Landing at the Beaver Island Marina, the Inland Seas nosed into the narrow fuel dock and we loaded gear into dock carts. Stopping for one last picture in front of the ship, those who were to leave on the ferry said their goodbyes and we started off down Main St. carts in tow. We hiked down the sidewalk of the sleepy little town, passed the King Strand Hotel and to the ferry dock. Leaving their gear with the ferry crew, we made our way to the Shamrock for lunch and a drink. The ferry departed at 5 P.M. with part of the FBET crew.

Back aboard the Inland Seas, we were now anchored out in St. James harbor, a few bunks emptier and a few voices lighter. It felt strange going on without a part of the expedition. We loafed around for a few hours, listening to forecasts and watching the radar, wondering if our already overlong trip would be extended again.

Just before sunset Captain Ben announced that the weather was breaking up and the wind was dying down. We would be able to make a break for Traverse Bay and the Inland Seas’ dock at Sutton’s Bay. The wind dropped off significantly, the skies cleared, and the western skies offered up a beautiful glowing sunset. We hoisted sails and headed south out of St. James harbor. As we came abreast of the island, the light winds carried the strong scent of cedar from the island and the sunset grew more vibrant with red and gold as another high storm cloud began to obscure the horizon.

As the horizon grew dim, we passed the southern tip of Beaver Island marked by the Head Light. The waves were still pretty high, but we were quartering away from them and under full sail. Night fell, and the dispersed clouds gave a view of the stars above. Captain Ben. Amid the flapping of canvas and clank of rigging, he gave us a lecture on celestial navigation, and the more basic art of wayfinding with stars as compass points. He pointed out the bright W of Cassiopeia, the dark spot that represents the Andromeda galaxy. He spoke of the stars and constellations visible in other parts of the world and how people found their position before the technology that we have today.

As the night wore on talk became sparse. Eyes toward the skies, rocked back and forth, an easy wind at our back, we finally relaxed. Exhausted with the days of bad weather, the truly awesome experiences, and with good friends all around; I racked out in my bunk full of wet gear, marking the end of my Beaver Archipelago expedition.