Beatin da Pat Nord (Translated form Newfie – Walking the Path North)

In 1771, a small party consisting of three married couples and eight single men landed on the coast of Labrador (then Newfoundland) led by a Moravian missionary, Jens Haven. They unloaded their small ship while the waters receded 2 inches per minute due to the outgoing tide. Eventually, the tide halted nearly 36 feet below its high level. This small party intended to start a mission station for the Moravian congregation from Saxony in Germany. These first missionaries set foot on a coast afflicted by constant war between Europeans and Inuit. They also happened upon a coast so remote and unforgiving that it would not see its first major road completed until the beginning of the 21st Century.

They founded the settlement at Nain. This was the first Christian mission to Inuit in what is now Canada. The Moravian congregation slowly expanded their Gospel and shaped most of what the region of Labrador was to become. Which is to say, not much more than it was.

Although Labrador was founded over 2 centuries ago, it has barely escaped its “settlement status”. It isn’t to say that time “forgot” Labrador, but more like “we’ll get back to you in a couple of centuries”. The citizens have cars, jobs, businesses, Facebook profiles and twitter accounts. For sure they argue about the same stuff everyone else does, they hold modern political beliefs and are just like the rest of North America.

For all the modern personalities, Labrador is still like a far flung group of colonies, struggling to survive against an unforgiving wilderness and the disconnection from the rest of the world. For instance, the settlement of Nain, which is the capital of Nunatsiavut, is occupied by its 1,500 residents. One could conceivably point to two reasons that it Is actually doing as well as it is. First, from 1950 to 1990, the Canadian government forced the citizens of other smaller coastal settlements to relocate to Nain, which bolstered its population from less than 500. Second, Nain is still serviced, as it has been for 2 centuries, by relief ships that still transport all its residents, visitors and freight, except for a few flights a week that land at Nain’s gravel air strip.

The MV Northern Ranger is a ferry, heavily subsidized by the Canadian government. By some estimates, the Commonwealth provides 90% of the funding to continue ferry service. The ferry takes 2 ½ days to travel from its home port of Happy Valley-Goose Bay. Happy Valley-Goose Bay is one of the largest cities with 7,500 residents. For sure, if not for the support of the federal government, Nain and the handful of other settlements, might not exist today.

Labrador is so charmingly. . . so ruggedly remote that its only highway wasn’t connected to its eastern terminus until December of 2009, finally connecting the settlement of Cartwright to the rest of the world. The first phase of the Trans Labrador highway wasn’t completed, from Labrador City to Happy Valley-Goose Bay until 1992. Until that time, the only way to get to Labrador’s interior cities, was by snowmobile, airplane, dog sled or by foot.

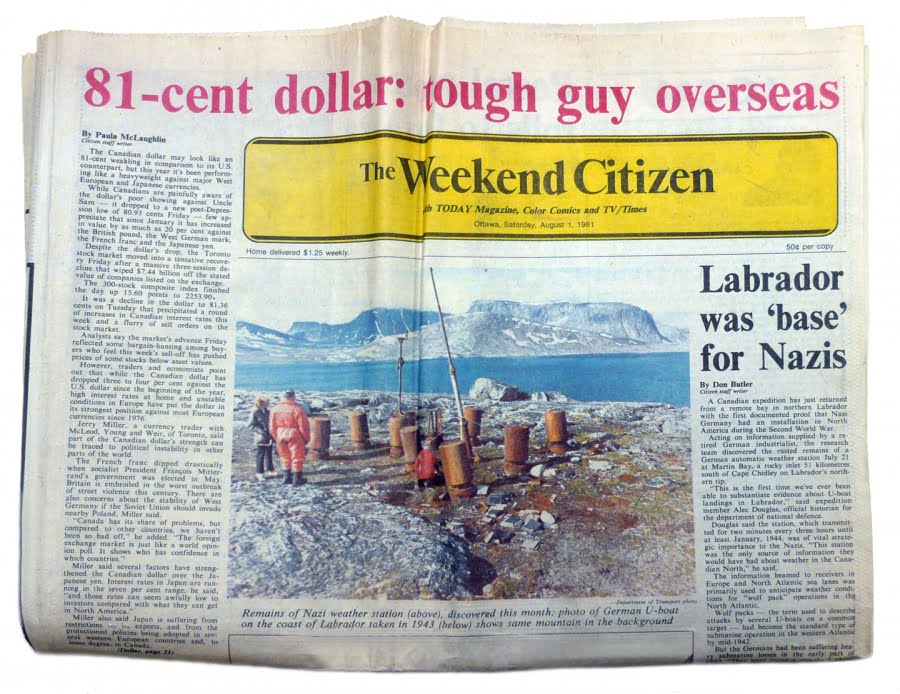

To further illustrate its remoteness, the northern tip of Labrador was host to the only known, armed, German military operation on North American Soil during World War II. In 1943, the German U-Boat, U-537, reached Martin Bay near Cape Chidley on Labrador’s Northern Tip and quietly dropped anchor. Their mission was to set up an automated weather station, code name: “Kurt”.

Within an hour of dropping anchor a scouting party had located a suitable site and soon after, the aptly named, Dr. Kurt Sommermeyer, his assistant, and ten sailors disembarked to install the station. Armed lookouts, no doubt adorned in fashionable pea coats, seafaring beards and eyes of chipped granite, were posted on nearby high ground and other crew members set to repair the submarine’s storm damage.

To conceal their sneaky scientific instrument, the station was camouflaged. Empty American cigarette packets were scattered about the site to deceive any Allied personnel that chanced upon it, and the equipment was marked as the property of the “Canadian Meteor Service”. The crew worked through the night to install Kurt and repair their U-boat. They finished just 28 hours after dropping anchor and, after confirming the station was working, U-537 quietly departed for Lorient, France.

The weather station only worked for a few days. But, for the next 33 years, it went unnoticed until a Geomorphologist named Peter Johnson, stumbled upon it. But he assumed it was a Canadian Military installation. Johnson simply noted it and moved on.

Then in 1981, a retired Siemens engineer, Franz Selinger, learned of the station’s existence while researching the company’s history (Siemens had originally produced the station). He contacted Canadian Department of National Defence historian W.A.B. Douglas.

In the same year, a team was dispatched to the location and found the station still there. The canisters had been opened and components strewn about. Amazingly, for almost 40 years, the station remained undiscovered as it defiantly rested on Canadian soil.

You take my point of course. Labrador is a lonely place. In fact, you could fit the state of Michigan (both the upper and lower peninsulas) into Labrador. . . twice. Michigan has a population of 9.894 million. At twice its landmass, Labrador has a population of 28,628, a population smaller than the city of Port Huron in Michigan.

Today, the coast is dotted with a colorful host of abandoned seaside fishing towns, defunct whaling stations, rotting military installations, Polar Bears, icebergs and boats. Resettlement has taken its toll on Labrador, but it has left a place to explore, wonder and learn. This secluded place is awash in history and the tales of human endeavor. The people are surely worth getting to know and befriend.

So, here we are. This expanse is just under 1,000 miles from my door step. The Trans Labrador, perhaps the longest unpaved highway in the world (certainly one of the loneliest) is another 770 miles (over 1,000 if you include the road through Quebec). How could I resist following this lonely trek? Well, I guess I can’t, so let’s take a ride.

I hope to explore this expanse in real time. Posting dispatches and Satellite locations as I go. Exploring the history, modern projects and people of this vast and lonely place. We start today. I’m not sure where we will end up or how we will get there. But we begin our journey.

Let’s Go Farther.

-Pathfinder

This is the Trans Labrador Highway. Many people try to claim these pictures are of other locations, to make their snow storms look cool. But these are pictures of the TLH. The deepest snow usually occurs on the eastern section of the road.