Includes affiliate links that help offset our expenses at no cost to you.

What mode of winter travel is best? It always depends. Whether you should use skis or snowshoes depends on skill level, terrain, snow conditions, vegetation and many other factors. Simply said, “it depends”. Skis, snowshoes, or post holing all have their pros and cons.

The answer “it depends” always seems to be a little disappointing. “It depends” is an answer that doesn’t have any real value to us. But, the answer is the most honest and correct answer we can give. Simply, neither snowshoes or skis are the best in all conditions, some are better in some conditions, others are better in other conditions. It is just the the way this complicated business works.

That said, after a few years of research and experimentation, we can say that maybe there is a better way for almost ALL winter conditions. There might be a better way to take most of the pros from each category and and start a new category we will call the “hybrid”. The hybrid isn’t the best in all conditions, but it is the most consistent in almost all conditions. We investigate this possibility here.

To begin, let’s quickly review both traditional modes of arctic/winter travel.

In winter conditions around North America, we adventurers often travel on deep, non-consolidated snow, with fragile crust, and even on wet spring time snow (which, is hard in the morning, can deep to our armpits when thawing in the mid-day). These conditions necessitate some sort of travel gear. Traditionally, that gear has been either snowshoes or skis. Choose your equipment carefully because one is better than the other in different conditions. In fact, one will often be better than the other an visa-versa in the same trip. Here are some considerations:

- Terrain (flat, rolling, steep, flat, water crossings, heavy brush, rocks, sand, etc.)

- Distance

- Goal of trip (expedition, recreation, class, climbing, etc.)

- Skill level or experience

- Load/Gear Weight/Pulling a Pulk

- Type of travel gear used by the team

- Current conditions and Forecast

Snowshoes are the most popular among the hikers and hunters of the Great Lakes region.

Snowshoes are relatively slow but they benefit from being the lighter, more compact, and easier than other travel gear. You can easily maneuver through the bush, around tree wells, up hills, and across inclines pretty well. Modern snowshoes are lightweight, have aggressive crampons for climbing and crossing steep terrain. Snowshoes also attach to most boots.

Almost any novice can strap on a pair of snowshoes and be off and hiking. Most of us learned our snowshoe skills through the tried and true – 10-step lesson. We took 10 steps and had learned how to use them.

Modern snowshoes typically come in two types. Solid molded plastic snowshoes are simple to use, lightweight and tough.

The other style stretches lightweight neoprene material between a metal frame, such as models by Yukon Charlies and Tubbs.

Snowshoes are most efficient in deep snow and tight bush. Most modern designs however, require that we plunge one foot into the snow and create a big crater. Then, we have to lift it out before we can move forward. Doing this over a couple of miles is a full day’s work. If your snowshoes actually float on snow, you probably don’t need snowshoes.

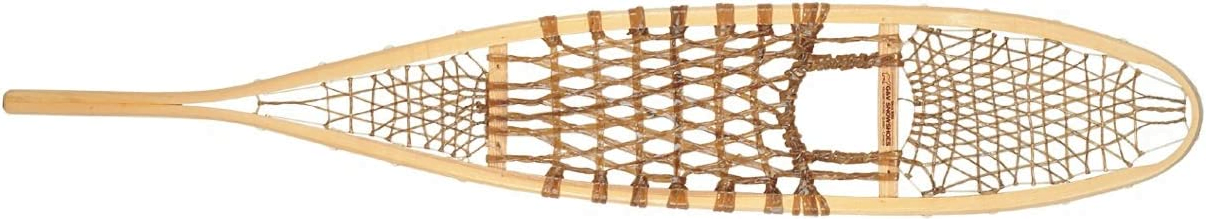

Older snowshoe styles can be better suited for trail breaking in deep, powdery conditions. When breaking trail in deep powder, modern compact snowshoes aren’t that efficient. Modern snowshoes are best suited for trails that have already been broken. Traditional snowshoes provide better floatation and are typically better for off-trail, deep powdery snow situations. However, they are typically larger and bulkier.

Most winter hikers take this simple solution, and they buy the warm boots, shoes and poles with baskets. With that, they call it good. Unfortunately, they’re inefficient in most terrain and pale in comparison when going downhill on skis. But, “skis take practice and skill”, you say? Most do – but not all. We’ll talk about that a little later.

While snowshoes work in a lot of scenarios, the progress they provide is often painfully slow and hard work. This is a limiting factor. A 15 mile hike in the summer might take a few hours; you can easily reach your destination in a day. On snowshoes, you might be doing an overnight.

AT (Alpine Touring) or Telemark skis are often a good choice for cross country travel in deep power. Bindings of both allow for the heel to be free for nordic (cross country) skiing. Both skies are normally used in steep terrain. Skis are much faster in certain terrain. You can travel downhill in a fraction of the time it would take to snowshoe there. On flat terrain with dense snow, they are much faster than shoes. Skis are less taxing in favorable conditions than snowshoes.

The downside is the cost, bulk and their learning curve. Skis, bindings and boots, in both styles, can easily cost up to a thousand or more for a full set up.

Traditional ski touring equipment is heavy, sometimes 3 – 4 times the weight of a snowshoe set. These ski packages are also too bulky to maneuver in crowded terrain. Having to deal with special boots, bindings and skis can add up on an expedition.

Both AT and Telemark also take a fair amount of skill. It takes time to learn and develop the needed skills to safely and efficiently travel by these methods. But once you master the technique, these disciplines provide a great way to travel in the backcountry.

So, snowshoes are maneuverable and lightweight, but not efficient. Skis are efficient and fast, but they are heavy and not very maneuverable in tight terrain.

It doesn’t take long to realize that ski gear and snowshoe gear are at opposite ends of the spectrum. Ski gear doesn’t fit with backcountry travel “far” from the groomed golf course trails or obscenely priced resorts. Each ski discipline caters to the right environment and the right conditions. Once tight terrain or snow conditions not suited to your gear are encountered, your progress slows to a “proverbial” crawl. Snowshoes work in those tight conditions, but your progress is almost always a tiring crawl. The solution we seek, as all-conditions adventurers, is consistency across all (or most) terrain & environment. A solution that is most versatile for most situations.

We seek the good things from both worlds, while limiting the bad things. We would like equipment that takes the strengths of both skis and snowshoes and minimizes the downsides. Are there products that can do that? Yes. . . yes there are. Read on.

There are actually a number of concepts that exist in the Hybrid category. Split boards, Marquette Skis, Karver Skis and a few more. Karver skis are no longer manufactured. Split boards aren’t really a solution as they are limited in the conditions where they work best. Marquette skis, while made for flotation on snow in the backcountry, have other downfalls that cause them to be undesirable in a lot of conditions – from climbing slopes, to turning in dense snow. They do offer some advantages, but not enough to be considered a “solution”.

One company called Altai seems to have developed an effective solution for backcountry winter travel, whether in ski country or tight terrain. Altai Skis were developed by Nils Larsen (from NE Washington State) and Francois Sylvain (from Quebec, Canada) in 2009. They claim their design was based on the skiers of the Altai Mountains in of Northern Asia. The idea was to base their design on skis used by skiers who ski everywhere – out their backdoor to feed their animals, visit a neighbor or embark on a hunting trip. Frankly, after we have spent a couple of years on the Altai Hok (pronounce Hawk), we believe they found the right inspiration.

The Hoks are lightweight, slightly more bulky than snowshoes and adapt to many conditions. The width of the skis allow for excellent flotation in powder and their short size allows for more maneuverability in the bush. The basic ski design allows the adventurer to “slide” their feet across deep powder instead of the arduous task of high stepping with snowshoes.

Sizes: The Hok comes in three sizes 99mm (for the kid skier), 125mm and 145mm. The 125 mm skis work best as a snowshoe substitute. They are very maneuverable in tight terrain and are very easy to use for the beginner. The 125s are lighter and have better grip.

The 145mm ski acts more like a ski and helps the “big” skier with suitable flotation. The 145s glide better, have more flotation and are more comfortable (and faster) going downhill.

Flotation: The size of the surface area on the Hok is slightly more than the common snowshoe with no space for the snow to push through. The large surface area seems to allow for better flotation than most snowshoes. The Hok (translated as “Ski” from one of the indigenous languages of the Altai region) has a very strong wood fiber layer that is both lightweight and tough to break.

Bindings: The Hoks come with 6mm stainless steel inserts that accept 75mm 3pin bindings and the universal xtrace binding (from Altai). The universal binding also offers advantages over other skis. You can use most any boot with the universal bindings. They are easy to use with 2 ratchet-able straps on each ski. The user simply sizes the binding (which fits a variety of boot sizes), inserts their boot, inserts the two straps and tightens with the ratchet.

The downside to the binding is they aren’t great on the downhill or on sidehills due to the flexible base. The 3 pin binding really improves performance in this area.

Altai also sells an adapter plate that allows for Rottefella NNN BC and Solomon BC bindings. Some customers have also mounted AT and Telemark bindings using Quiver Killers.

The stainless steel inserts also prevent having to “drill” the skis to attach bindings.

Mount: The bindings on a Hok are mounted forward. This forward mount allows for more maneuverability and ease of use. Also, by mounting the bindings slightly forward, the ski does a great job of breaking trail in new powder.

Ski Surface: On the underside, the Altai exceeds the features of most other ski shoes like the Marquette. The Hok has integrated synthetic skins that work for steep climbs and control the speed of descents. If the skins are damaged, they are replaceable by a reasonably skilled do-it-yourselfer. Though you can wax the underside for “sticky snow” the bottom performs well without waxing in colder conditions.

There is also a full steel edge to protect the skins and for edge hold on firm snow. The steel edge is an important feature the separates the Hok from other competitors in the skishoe market.

Maintenance: Not much. The company recommends checking the screws on the bindings to make sure they are tight. We used loctite on the screws to keep them snug. They recommend keeping them in a dry place (not stuck in the snow) and if the bases are dry, rub xc paste wax or hard (glide) wax on them. If the skins start to wear or begin to detach, you can replace them.

Our tests of the Altai Hoks prove that it is a rugged little ski with good performance in a variety of terrain and conditions. We have pulled pulks, skied tight trails, broke new trail in deep powder and explored areas well beyond snowshoe range.

When considering equipment for winter outings, the Hok proves a worthy piece of gear that performs well in a wide variety of situations. It isn’t the best in all categories, but good enough from most. That makes this tool a great addition to an explorer’s gear cache. Give them a look.

See also: How to Travel in High Risk Snow Areas,

The Best Foot Traction Devices for Ice and Snow